The future still belongs to just 'the right kind of people'

The seductive power of Victorian thinking about the relationship between character, technology and the future remains pervasive

Throughout history, men with access to superior technology, money, good ideas, skills and a deep yearning for power have set out to colonise others by imposing their ideas, stories and culture on others, so that they become ultimately economically and socially reliant on the new systems that the 'pioneers' bring.

This pattern of 'innovation exploitation' is as old as history.

In the 17th century The Dutch East India Company exploited their superior access to finance, shipping technology and global navigation to forcefully exploit numerous territories from Africa to the Far East.

Their innovative ideas and systems gave rise to many of the economic systems that we still make use of today.

'In 1602 shares in the Dutch East India Company were issued, suddenly creating what is usually considered the world's first publicly traded company.'

'The VOC played a crucial role in the rise of corporate-led globalisation, corporate governance, corporate identity, corporate social responsibility, corporate finance, modern entrepreneurship, and financial capitalism. During its golden age, the company made some fundamental institutional innovations in economic and financial history. These financially revolutionary innovations allowed a single company (like the VOC) to mobilise financial resources from a large number of investors and create ventures at a scale that had previously only been possible for monarchs.'

The VOC not only exported their own particular brand of capitalism throughout the world, they also very successfully promoted their culture and ways of thinking too.

Roman Dutch law is the system of legal practise that we still use to this day in South Africa and Afrikaans is still the country's third most spoken language.

America's greatest export is not produced in a factory in Detroit or on the farmlands of North Dakota - it's made in Hollywood, and increasingly these days - coming out for Silicone Valley.

America's #1 export is its culture and its stories.

In the 90's the focus was very much on entertainment and the colonisation of the world's perception through news media assets like CNN :

'Entertainment around the world is dominated by American-made products. It's "The Young and the Restless" in New Delhi, Garth Brooks blaring from a Dublin apartment, or the eager line of people waiting outside a Nairobi movie theater to see "As Good As It Gets." It's Bart Simpson in Seoul, Madonna in Sao Paulo, "Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman" on Warsaw TV.'

And who doesn't remember watching the start of the Gulf War in 1991 live on CNN, or where they were when they watched the second plane flying into the World Trade Centre in 2001?

Now the new colonisers of the future are people like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos.

Their ideas and inventions carry far more weigh and influence than anyone else's; even though what is being produced by their imaginations is not necessarily what it best for the world at large, but rather what is best for them.

The future, according to Musk, Zuckerberg and Bezos et al., that we blindly consume is literally taking us back in time. Back to the glory days of colonisation and subjection by powerful individuals with the intent to extend their power and influence.

This is a particular style of futurism - a narrow, singular view of the future - that is most certainty not more relevant than any other way of seeing the future, but one that people are heavily influenced to adopt for themselves.

'Reproductive futurism and what we can think of as the “corporate futurism” of traditional innovation both favor superficial progress and narrative sequencing, “not toward the end of enabling change, but … of turning back time to assure repetition,” writes Edelman. Under reproductive futurity, we are collectively biased towards non-disruptive and incremental change, and against the radical, queer, or truly revolutionary that threatens the so-called “natural order” of biological sex, family values, and economic growth. So-called realism has trapped us in an interminable present, where even the most daring innovations fail to envision a better and more equitable world—and in fact depend on the failure of our imagination for their successes, if you consider how Amazon’s delivery-on-demand has merely set a precedent for further deteriorating working conditions; or that Elon Musk’s Hyperloop only makes sense in a future without public access to transit; or how Meta can only envision alternate-dimensionality as an office-cum-mall that hasn’t even corrected for landlords.'

So what's the alternative to this particular style of future propaganda that is being sold to us by these billionaires?

'As we contend with the prevailing uncertainties of climate chaos and narrative collapse, and reach new heights of capitalism-cynicism, we’ll see increased interest in futures beyond the affliction of normative futurisms; futures which break rather than perpetuate the status quo. If normative futurisms value difference only in order to exploit or overcome it, continuously reduce social relations to the unit of the individual, and coerce us into thinking planetary problems—such as hunger, extinction, and climate disaster—are practically unsolvable, how can we then construct a future constituted of difference and collectivity? In the words of the artist Sin Wai Kin (fka Victoria Sin), “How do we envision a future that isn’t a way forward, but a way down?”'

What if our planetary vision of the future wasn't one that was sold to us by self-serving white guys sitting in Silicone Valley?

'In recent art and film, ideas around divergent futures have crystallized in the form of ethno-futurisms, such as Sinofuturism, indigenous futurism, and contemporary Afrofuturism. Many present alternative scenarios to Western progress predicated on revising history or reimagining geopolitics. Indigenous futurism and Afrofuturism, for example, raise the query, what would science, technology, and industry look like if it did not depend—as it does now—on environmental extraction and human subjugation? Yet others, such as Sinofuturism and Gulf Futurism, simply ask, how would we see the future if the core concepts of “progress” arose from somewhere that wasn’t the West?'

Considering the fact that the future has since way back to the 17th century, been dominated by, owned and served to us by powerful individuals and companies from the West, how likely is it that we will be able to break this pattern of obedience and start to listen to and believe in alternative visions from new places?

The evidence in this regard is not great.

'Tech titans like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos present themselves as men who could single-handedly shape the future. For their supporters, their ruthless drive toward success is their key virtue. And their showmanship — Musk sending a Tesla Roadster into space on a Falcon Heavy rocket, or Bezos sending Captain Kirk into orbit with Blue Origin — is a way of demonstrating that virtue and asserting they are in control.'

'We owe it to the Victorians the idea that there is a firm link between virtue and technological agency. They established a powerful paradigm that continues to haunt us: that the future is (or can be) a utopia, and inventors and entrepreneurs are the ones who know how to get there.'

'While our notions of virtue have shifted today, we still assume that future-making is the prerogative of very specific sorts of innovators — even as their imagined identities have fractured and transformed. The assumption that innovation is the property of charismatic individuals still underlies the way we think about technology.'

'The future belongs to just the right kind of people.'

'Thomas Edison, dubbed “The Wizard of Menlo Park” by the New York Daily Graphic in 1879, knew perfectly well that he needed to cultivate a persona that matched the public’s expectations of what a man of invention should be: rugged, self-made, self-assured, self-reliant — a powerful and politically resonant image in late nineteenth-century America. This was the practical engineer, distrustful of intellectual elites, ploughing his own furrow and laying down the foundations of an American future in the process. Invention in the Edison style was meant to be about pioneering know-how and a dogged determination to make things work. Edison’s virtues were the virtues of the frontiersman, except that the frontier he was trekking toward was the frontier with the future.'

--

'The seductive power of Victorian thinking about the relationship between character, technology and the future remains pervasive, even if views about just what the proper character of the inventor should be have shifted. Edison today is celebrated as the hard-nosed business inventor, generating patents like a one-man factory of invention, while Tesla is seen as an iconoclastic, rule-breaking outsider who refused to conform to the dictates of the market. Tesla himself assiduously promoted that image, presenting himself as the man who could single-handedly make a future in which men would be as gods. It’s no coincidence that Elon Musk chose to name his company after him.'

Sadly we have to agree with the conclusion that is is reached by Iwan Rhys Morus in his article recently published by Noema; the powerful, charismatic individuals that are currently shaping the future of the world are never really questioned as to what their intent is or exactly who their inventions are meant to be serving.

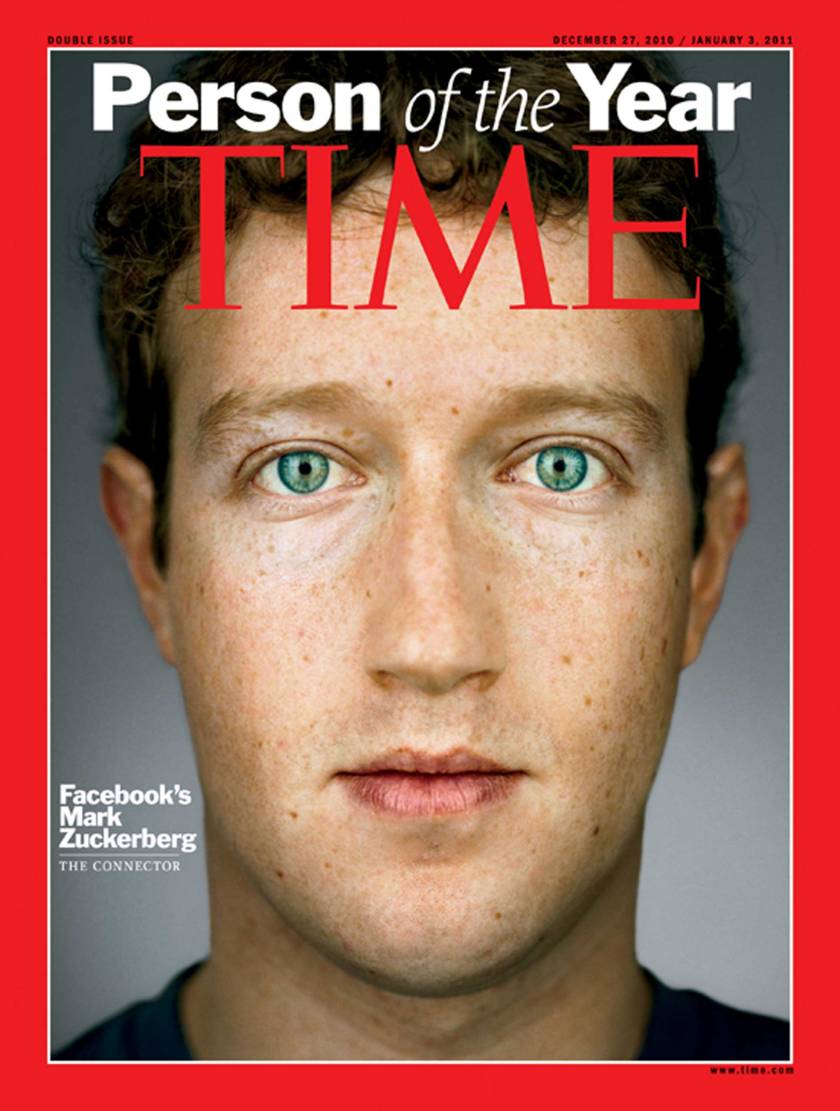

As long as the stock prices of the companies that they represent are going up and they continue to be seen as selling a utopian view of the future,; they are plastered on the front-pages to powerful magazines and blindly lauded by all as gods of the world.

As one of our favourite authors, Douglas Rushkoff, puts it:

'Digital futures became understood more like stock futures or cotton futures — something to predict and make bets on. So nearly every speech, article, study, documentary, or white paper was seen as relevant only insofar as it pointed to a ticker symbol. The future became less a thing we create through our present-day choices or hopes for humankind than a predestined scenario we bet on with our venture capital but arrive at passively.'

Their power is however an illusion, a dangerous trick of the mind that will continue to ensure an inequality of voice and a type of future monoculture that truly benefits very few.

The reality is that a better, equitable, human future doesn't belong to an individual, rather it's a collective, diverse vision that includes and benefits all of humanity.

Sources: