The future of crime in the year 2054

How will technology develop from now until then, how will business react, in what ways will that affect society - and how will politicians then try to put the flames out with their policies and regulations?

To understand crime in the year 2054 - we need to understand what the world will most probably look like in 2054.

How will technology develop from now until then, how will business react, in what ways will that affect society - and how will politicians then try to put the flames out with their policies and regulations?

Which is exactly the process that Steven Spielberg followed in creating the 2002 blockbuster film Minority Report.

Peter von Stackelberg and Alex McDowell wrote a paper, 'What in the World? Storyworlds, Science Fiction, and Futures Studies', which goes into considerable detail as to how Spielberg went about creating a unique future story-world in which the movie was set; long before the script was written.

I have taken the liberty of posting some of the highlights from that article here.

What in the World? Storyworlds, Science Fiction, and Futures Studies

The futuristic technologies in the 2002 film Minority Report, an action- detective thriller set in Washington, D.C. in the year 2054, have been widely noted for how prescient they have been.

While worldbuilding had been used before for science fiction projects, Minority Report took the process to a new level of sophistication.

The previous script for the film had been thrown out when Spielberg took the project and it took many more months than expected to complete the new script. In lieu of the customary text, the film’s designers were effectively obliged to develop the storyworld prior to the script. Because the script then took much longer than expected to deliver, the process became a radical departure from the norm of film production to date, or since.

Another critical factor was the falling cost and rising performance of computer technology, which brought conceptual and 3D visualization into the design department for the first time. This allowed not only designers, but also the producers, writers, director, and other members of the production team to share in the visual and story development process through immersive design visualization and prototyping.

As a very different example of disruption, a digital visualization process was developed as an urban planning tool to help resolve the design of the world. A 3D model allowed for iterative development of the rules and logic of the world. This process involved examining the scale and location of fictional elements relative to the real world geography and terrain of Washington DC, infrastructure, architecture, urban development, and transportation systems.

McDowell approached architect Greg Lynn and some of his young architecture students to join the design department, where they used Maya 3D animation software to radically change the traditional film design process and incorporate it into the world build.

McDowell also hired car designer Harald Belker, who brought with him the 3D tools he had been using at BMW, to design the unique vehicles of Minority Report. One of these vehicles was conjoined with the vertical design of the new architectural city to create a vertical and horizontal transportation system. The final vertical car stunt sequence in the film was almost entirely produced in post- production but it was designed, prototyped and developed using 3D visualization. Not only was Spielberg able to direct the digital animation long prior to shooting, but he was also able to approve 3D printed moquettes of the vehicles and then see the same digital data used to manufacture the final car for actor Tom Cruise to interact with at full scale.

In the past, many of the decisions for these sequences would have been made in post-production during visual effects development, but with Minority Report that old linear process was upended and replaced by an entirely non-linear collaboration in the early stages of production, prior to shooting.

These new applications of digital technology in developing the narrative logic for story and production resulted in a rich storyworld with a unique level of consistency of vision for the film.

Another key factor in shaping the film was director Steven Spielberg’s requirement that Minority Report be approached as future reality, not traditional science fiction.

He did not want to allow his audience to escape the implications of the film’s outcome of the film by dismissing it as simply science fiction.

Spielberg locked in a few key elements of the story, which was already radically changed from the 1956 Philip K. Dick short story on which it was based: it would be set in Washington DC in the 2050s; it would be a benign and apparently utopic future world with no fossil fuels, sustainable and ecological, with technology that works and augments the society and political, cultural, economic and technological systems; and at the heart of the film would be the primary societal disruptors – the Precogs themselves.

Their ability to predict violent crimes and apprehend the perpetrators before they commit the crimes results in Washington DC becoming a murder-free city. This in turn leads to a massive population shift to the Washington DC area, which in turn leads to the development of a new vertical city and a highly stratified society.

With Spielberg looking for a future reality that fit within those parameters, the processes of narrative design and the visioning of innovative technologies and urban environments were not simple. Typical movie design research involves in-house designers and usually a single researcher gathering information.

The process for Minority Report was much more sophisticated.

How did they create the Minority Report story-world?

Spielberg and producer Walter Parkes had convened a group of experts for Jurassic Park with great success. Without a developed script, McDowell and Frank worked with Spielberg determined to create an initial approach to a comprehensive near-future world through conducting in-depth research with experts in architecture, engineering, urban planning, advertising, art, science and technology, and politics.

In 1999, they took the first step in the research process by engaging in multiple weeks of internal design research.

At that initial meeting, the first level of detail of flying vehicles and weaponry was provided by Dr. Shaun Jones of DARPA, and other members of the group provided a wealth of discussion and information about the ways in which this future city might develop, with its initial logic of society, politics and urban development framed by the demands of the story.

In the two-day gathering, the group sliced through this future world, looking broadly at a very diverse set of conditions. This was the first glimpse of what would become the world building process for the film.

Writer Douglas Coupland produced a highly tongue-in-cheek 100-page document of the future in 2050 specifically for the futurists and designers gathered together for Minority Report that was highly simulative for the group. It is interesting to note that the interplay between the traditional ‘futurist’ approaches – based on current, real- world constraints – and the storytelling demands created a valuable creative tension.

The steps:

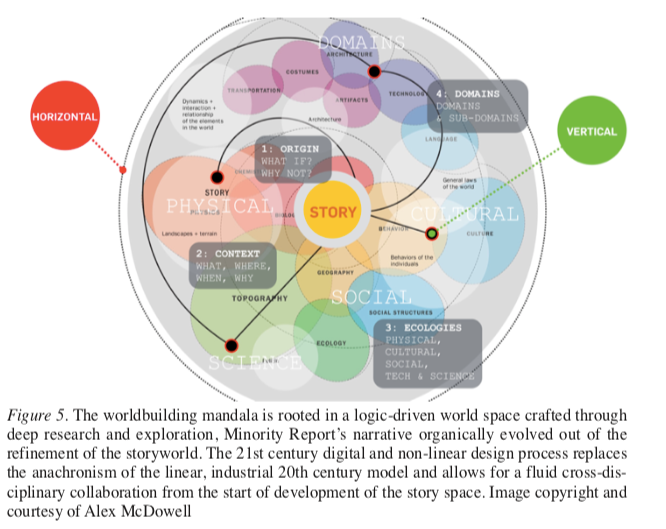

The Minority Report story-world framework was initially developed by McDowell in 2004 to describe the radical change put in place by his world building process. It shows that after an initial impetus from the story origin, the first approach is to what disruption in the narrative would stimulate the interrogation of the world.

This first stage is known as “What If and Why Not”. In this case the story

impetus of the Precogs – “What if there were three precognitive beings who could predict murder and allow Precrime Police to arrest perpetrators before they commit the crime” – leads to a question of range, whether this is an experiment unique to DC, and in turn to a massive influx of population to get the benefit of the murder- free society, leading to the need for rapid urban development.

This is contextualized by knowing where and when the story takes place, which brings real world constraints like the zoning laws in DC into direct relationship with the fiction of the narrative. At three broad scales – the world scale (the larger urban conurbation), the community scale (the new Mall City), and the individual scale (Anderton’s apartment, his car, and his artifacts) – the world begins to fill in with connective rules that develop a holistic logic-driven world space. The overview indicated in the framework represents a Horizontal slice through the world – all the major elements of society, culture, politics, science, technology, history, infrastructure and ecosystem that interconnect the narrative elements of the world.

To develop the fine detail of the world, the world builders then engage in a series of Vertical ‘core samples’ that interrogate the world system in relation to specific elements that have a direct impact on the narrative. These detailed investigations demand answers of the ecologies and domains of the world that in turn tighten the logic.

The deep research by the design team offered up robots based on insect behavior, non-lethal weapons, driverless cars, eye-tracking, voice command of computers, holography, optical tomography, heads-up displays, personalized advertising, even cloud computing. An exploration of smart elevators, maglev vehicles, and driverless taxicabs stimulated the prototyping of a three-dimensional transportation eco-system. McDowell’s process was to “extrapolate forward” – if Amazon has established a relationship with the consumer that allows personal data tracking to evolve into “if you like this, you’ll like that”, then why would that not extend to targeting consumers in real time in advertising and store point of sale.

The research process became an essential part of the narrative design and prototyping of the world of Minority Report, extending through the first year of development and establishing an unprecedented collaboration space for director, designer, writer, and the whole production team.

The 2050 Bible

All of the information gathered was assembled into an 80-page encyclopedic vision of the storyworld. This document – dubbed the “2050 Bible” by the design team – combined found images, custom illustrations, and text to set out details of the science and technology, cultural, and socio-political aspects of the story. The document became an important resource for the design department and all key creators as they came into the film. Incorporated into the 2050 Bible was a series of white papers written by design scientist John Underkoffler to provide the “science” for a multitude of elements that required a greater degree of detail, both in the design and as drivers for story.

For example, in the Precog Chamber (the Temple) the quantum physics that became the underlying logic for the precogs, determined the milky liquid in which they float, the optical tomography extracting the images from their precognitive minds, the intricate CNC-cut interior surface that was ‘sound- proofing for the mind’, the gesture language, the machine parts of the transparent computers, and the “red ball” system were conceived as an interconnected set of narrative triggers connecting to the larger world aspects of the precogs, the contrasting aspect of them in a public sculpture, their range and influence, their deification.

The 2050 Bible and the research behind it developed into a viable way to contextualize the future for the film. The investigations of the design team and the deeply researched ideas set out in the 2050 Bible directly stimulated narrative elements based on story-world vehicles, weapons, building interiors, and urban landscapes as well as the interactions between characters and the various story-world components. For example, the three-dimensional transportation system emerged as a design prototype, which in turn prompted the addition to the script of a new chase segment called the Vertical Car Chase. It became clear that the traditional scriptwriting process – the classic image of a writer sitting in a bungalow in the Hollywood Hills creating a stacked 120 pages of a script (McDowell, 2015) – could not provide the layered and integrated detail that the world building process developed.

The connection between the design vision and the accuracy of prototypes of near-future technology in Minority Report demonstrates the power of worldbuilding and interrelationship of science fiction storytelling and reality. When the film’s design team visited the innovation labs at MIT or spoke with experts at Apple, Lexus, and DARPA, projects viewed were often 10 to 15 years from fruition. Clearly, more than a series of “genius forecasts” helped shape the Minority Report story-world.

The complex evolution of a story requires interactive design of physical, political, cultural, and other environments and systems. What is clear from the worldbuilding process developed for Minority Report is that the combination of deep research feeding a logic-driven multi-disciplinary and collaborative story-world can provide rich narrative outcomes as well as significant insight and foresight. It is not an individual series of foresights from futurists but an organic evolutionary process centered in storytelling that allowed the emergence of a holistic fictional world that was genuinely “precognitive”.

Conclusions

Scriptwriting instructor and story consultant John Truby states that you set a story in the future to give the audience another pair of glasses, to abstract the present

in order to understand it better.

It might also be said that foresight professionals should set the future in a story (and story-world) so the audience is better able to experience it.

As our society develops and changes, both futures studies and science fiction can be used to show what will happen if we continue along certain paths. The freedom that worldbuilding allows makes both futures studies and science fiction more powerful by applying creative imagination to real conditions and then extrapolating forward and outward.

The worldbuilding process fits well with a number of theories and approaches that have influenced futures thinking and methodology:

- The creation of story-worlds is a collaborative knowledge building process that is consistent with the principles of social constructionism.

- Integral theory and integral futures call for futures methods that look at issues from the subjective, intersubjective, objective, and inter-objective perspectives. Story-worlds can provide a venue for including all of these perspectives in a foresight project.Sense-making is a process by which people’s experiences are given meaning. It is a social activity involving storytelling and shared conversations, with participants simultaneously shape and react to their environment. (Currie & Brown, 2003) Story-worlds can provide an open, evolving, multi-participant environment from which the meaning can be developed through the stories that are told and the conversations that are shared.

- The role of narrative in futures studies is not new. Whether it is the futures narrative creative process described by Schultz, Crews, and Lum (2012, p.137), the future-focused transmedia narratives described by von Stackelberg and Jones (2014), or design fiction described by Stein (2014), narrative is playing an increasingly significant role in futures studies. As storytelling both inside and outside the futures field becomes increasingly sophisticated, the importance of storyworlds and worldbuilding grows

- Some futurists may be wary of science fiction treading on territory that they feel is better left to futures studies. However, science fiction does play a major role in shaping popular perceptions of the future. The emergence of science fiction prototyping to explore technological and urban futures based on science fiction is showing how science fiction can play a meaningful role in shaping technologies and cities.

Worldbuilding should be central to all of these approaches to constructing and exploring the future.

Story-world development for Minority Report involved a smaller group of participants and the results were much more tightly focused on producing that story-world for a film. However, in both cases deeper insights into the future emerged as the story-worlds evolved and grew because of the contributions of multiple participants. While worldbuilding and the use of story-worlds is not the only method for working collaboratively, it is one of the most effective methods available for developing deep, rich narratives that lay out visions of the future.

Worldbuilding is a powerful futures studies tool that I have personally used to very good effect with a number of bold clients; including Dimension Data and British American Tobacco. It brings foresight research alive and give the audience a good reason to emotionally invest in a future vision and make it their own. Most business strategy fails because staff cannot see themselves as part of the future that is being poorly communicated - worldbuilding changes that. And long may the development of this cutting-edge synthesis of art and science grow.